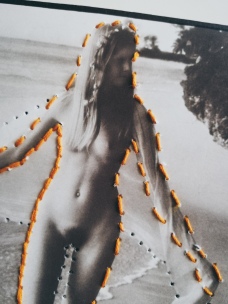

I have a longstanding habit of painting double portraits. There is something calming about a balanced pair, in both concept and composition. Spaced out harmoniously on canvas, two individual subjects depicted as a complimentary coupling – if there ever was a trope in painting that gets repeated over and over again, this one is mine. My latest canvas, Two Brides, is a perfect example of my obsession with twinned subject matter, special only as it features people rather than static objects.

The other reason Two Brides stands out from my previous double portraiture is its basis in photography. Generally, I would prefer to paint physical objects and still lives. This is my comfort zone, if you will. Unlike traditional portraiture with a sitter or an artist’s model, I am free to focus only on the surface of the subject being painted, without the need to acknowledge the feelings and needs of another sentient person. An object does not move, nor does it complain about the lack of loo breaks. The benefit of painting from photographs is in their fixed nature. An image is the perfect model, unmoving and always perfectly composed, but the benefits of photography are far wider: Simply by possessing the right snap, a painter is transported to a carnival in Venice, depths of the seven seas… even space – all in the comfort of the artist’s studio. On the flip side, however, why take the effort in painting a photograph when you already have access to an image, in essence, a finished piece of art?

Photorealist movement aside, using photographs as a visual aid when it comes to figurative painting is a highly contested matter. I know painters who openly look down on others who paint with the aid of photos and I too have reservations on work that relies solely on copying another image without any further curatorial input. Especially as a student, the prevalence of these types of attitudes kept me from considering photography as a tool, even when it would have aided my research beyond regular drawing or sketching. The only times I felt painting from a photograph was appropriate, for me, were cases when I had no access to the types of objects I wished to depict. My Volvo-pieces from 2011-2012 are a great example of this type of work – the cars in question have long rolled into the big car park in the sky and only exist in my memory… as well as selection of snaps in my family album. It took years and a bit of confidence to admit how I research my paintings does not need to reflect someone else’s view on what good painting should be.

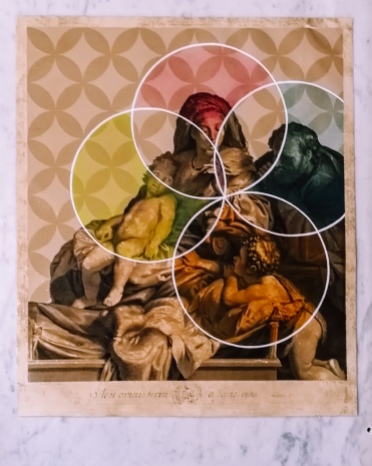

The fact of the matter remains that photography is widely used as an aid when creating visual art, sometimes directly, sometimes indirectly. Painting does not exist in a vacuum and should not be confined to early 19th century sketching methods for the sake of purity that never existed in the first place. From Vermeer and his usage of camera obscura to the angst ridden art student I used to be, photography is a valuable tool that allows us to capture fleeting situations and moods like no other creative medium. I would personally argue the usage of photographs has made figurative painting more inclusive and easier to approach. Not every aspiring painter can access live-model classes and galleries packed full of classical plasters waiting to be studied – this being the way you should be learning figuration in the minds of absolute traditionalists. Photography, in short, offers many their first contact in drawing a likeness and should not be dismissed due to its availability to all demographics. Copying the works of the old masters is a long established tradition in art education and replicating a photograph in paint can be just as enlightening when it comes to learning colour-matching and composition.

Figurative artists who prefer photography over sketching create work just as creative and painterly as those who do not. I am choosing to illustrate this point further, not with my own work or that of my friends, but by encouraging you to study the works of Peter Doig, a Scottish painter who utilises photography in his creative process. I visited his retrospect in the National Gallery in Edinburgh more than five times in 2014 and the show had a profound impact in my view of figurative painting and colouration at the time. I felt tight of breath standing in front of those wall-sized canvasses, bewildered by the wonder of Doigs brushstrokes. Few would argue his work is anything but engaging, original and impactful simply because his research includes photography alongside drawing.

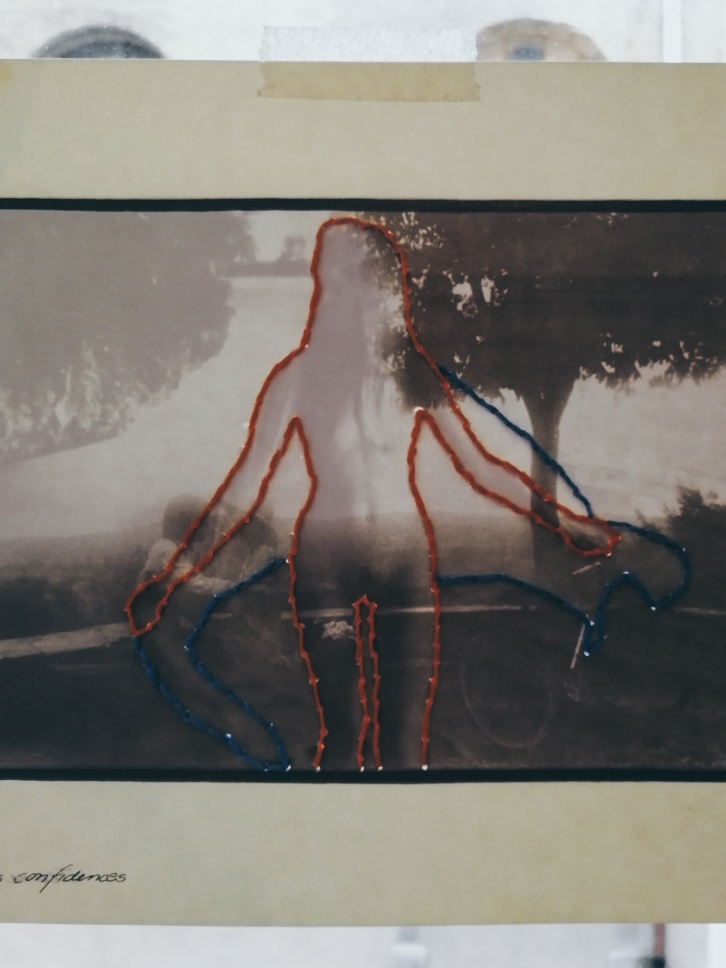

I hesitated for a moment before choosing to add snaps of my own research material for this particular blog. Two Brides is directly based on a set of wedding photographs from the early 1930’s. There is no way around that. I made a sketch or two from these images, but the final composition was simply crudely photoshopped together to act as my guide when painting. Combining elements from two photographs into a single double portrait is not difficult by hand, but utilising a bit of tech in this case made the process a lot faster. Does this make me less creative or worse off as an artist? In my own mind, the answer is irrelevant as long as the painting I am creating can be viewed as more than a collage of images taken long ago.

All I can say is that I cannot wait for this one to be finished.

Ta, Tiina x