Anybody else struggling with motivation lately?

Seems like this is all I talk about these days; I am not really built for the anxieties of the new normal. Where I tend to be pretty good at setting my own goals and sticking by them, lately the uncertainty with work and life in general has really started to affect my productivity. Add in a generous helping of self-doubt and you end up with this hard-to-shake feeling of existential dread.

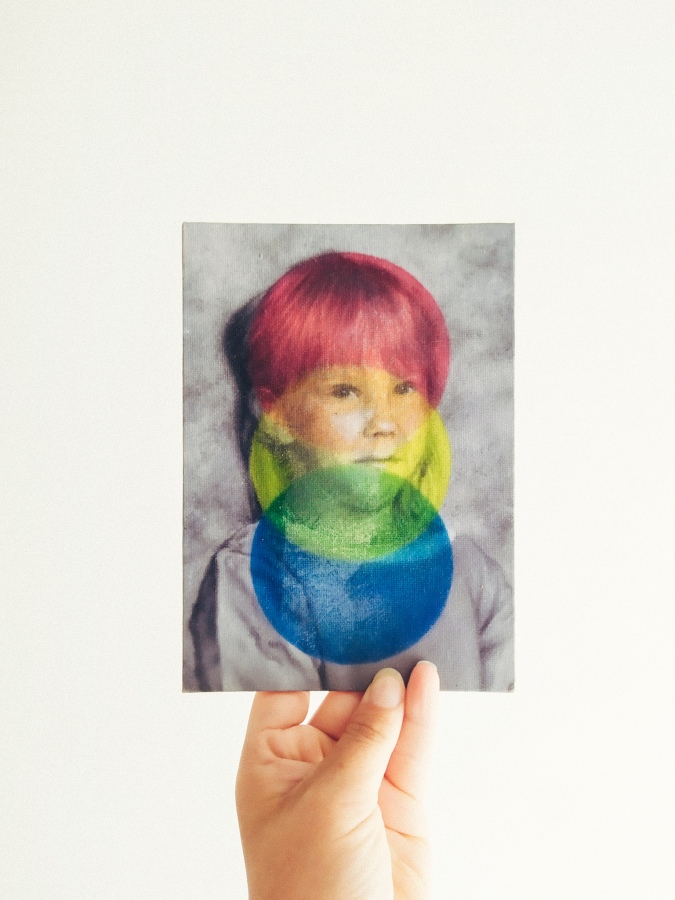

Not the best of times to revisit a finished artwork, I know, but here we are. Remember “1997” – I wrote a blog about the meaning behind the picture some weeks back and logged it as finished on my studio inventory. Case closed. Yet I have not stopped thinking about the wee thing. It is a piece that means a lot to me, being a sort of self-portrait and all, but I kept thinking it should somehow be… well, better.

This is by no means the first time I have started again: just last summer I completely repainted one of the faces in Two Brides. It was a calculated risk that paid off, but not an easy decision to make at the time. The materials I work with, mostly oil- and acrylic paints, are non-reversible. They can be removed using solvents or brute force for sure, but generally speaking you cannot restore areas that are overpainted once the paint has dried. A strict one-way system of sorts. The reason a conservator would use specialist pigments in restorative overpainting is so that their work can be safely removed when necessary. As an artist however, a maker of things, this is not a practical way to build artworks.

Personally, I thought the multi-coloured elements I added on top of the black and white portrait in 1997 were a bit heavy handed. I did not want to remove this layer fully, but rather integrate it better with the portrait underneath, by making areas on the face more translucent. I could have added more paint, or sanded down parts of the coloured top layer, but I opted out for a riskier strategy of a solvent, turpentine to be precise. The main reason I felt this painting was not working previously, was the dull precision of its parts, making it all too uniform for my taste. By choosing to remove some paint in this unpredictable way, I managed to re-introduce character that I felt was previously lost.

I am really pleased how it turned out, but again it was not a decision I took lightly. At the end of the day, any artist is responsible for their own quality control. Is this piece sign-off quality? Could I be displeased about it simply because I feel down about most of my work just now? Is the time used reworking this piece time/money well spent? Question yourself before taking steps that are irreversible. Measure twice, cut once etc.

If you need to think whether an artwork is finished, it probably is not. Conversely, there is a fine line between sensible quality control and micromanagement. You can set any picture (or a problem) aside and return to it when you are feeling better/more confident/re-inspired.

Or simply, ask a friend – if there’s one thing I have learned from the Covid-19 crisis it is that we’re all in this shite together.