Proximity /prɒkˈsɪmɪti/

noun

nearness in space, time, or relationship.

I’ve had some great news last Thursday: I’m finally going to be off furlough and back to work as a studio painter. It has been a privilege to dedicate this much time for making my own art, but to be completely honest, I am really keen on returning to a form of normal in September.

Unlike my husband who has been working from home throughout and following lockdown, I have needed to set my own challenges during the Covid-19 crisis. I would definitely say I was in a bit of a creative slump before the pandemic and the only way to move forward towards the new normal was to change the way I make art. Focussing only on the positives, the last several months have made me more confident in exploring new ways of making visual art as well as tackling more overtly personal subject matter than ever before. The first of these experiments, begun in early spring and finished in late July, is Proximity: a piece about my father who I haven’t been able to see since last summer.

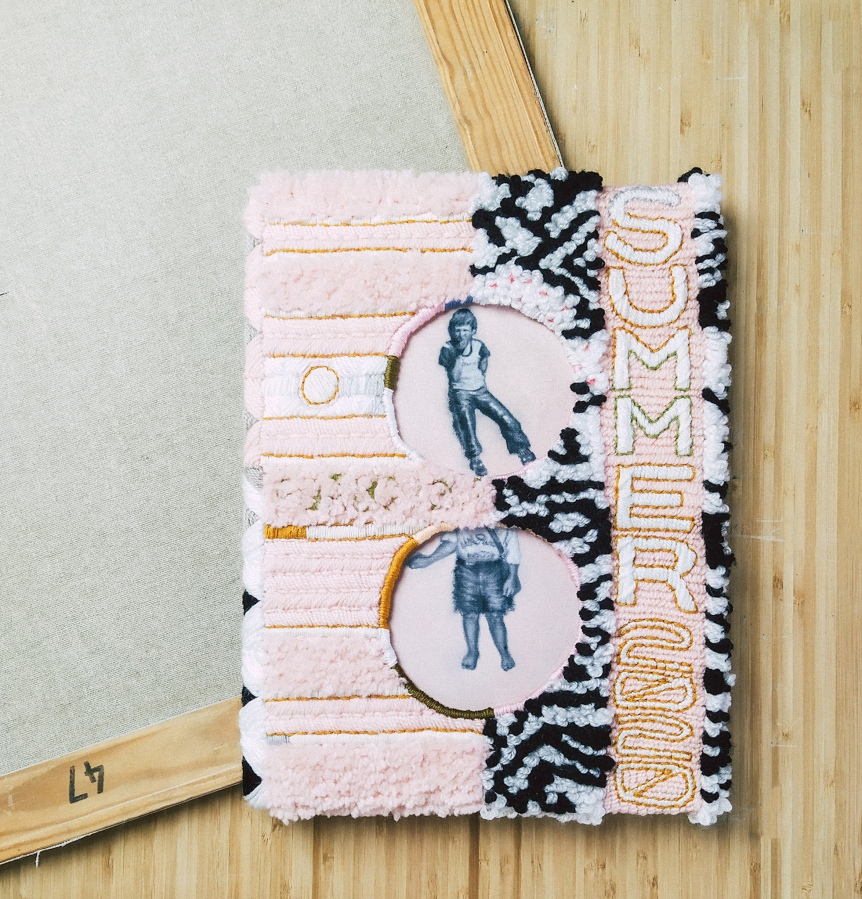

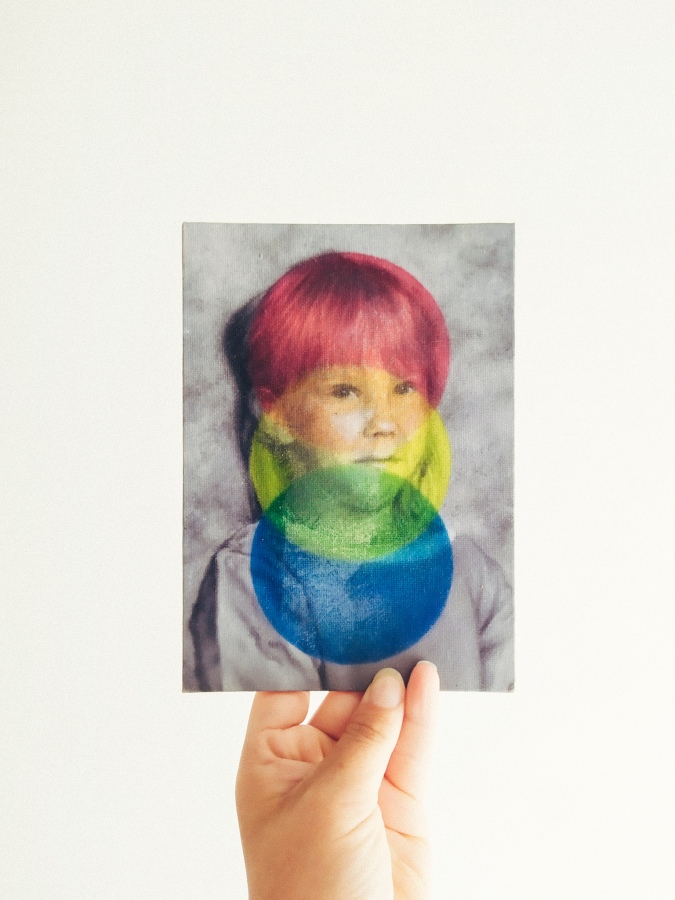

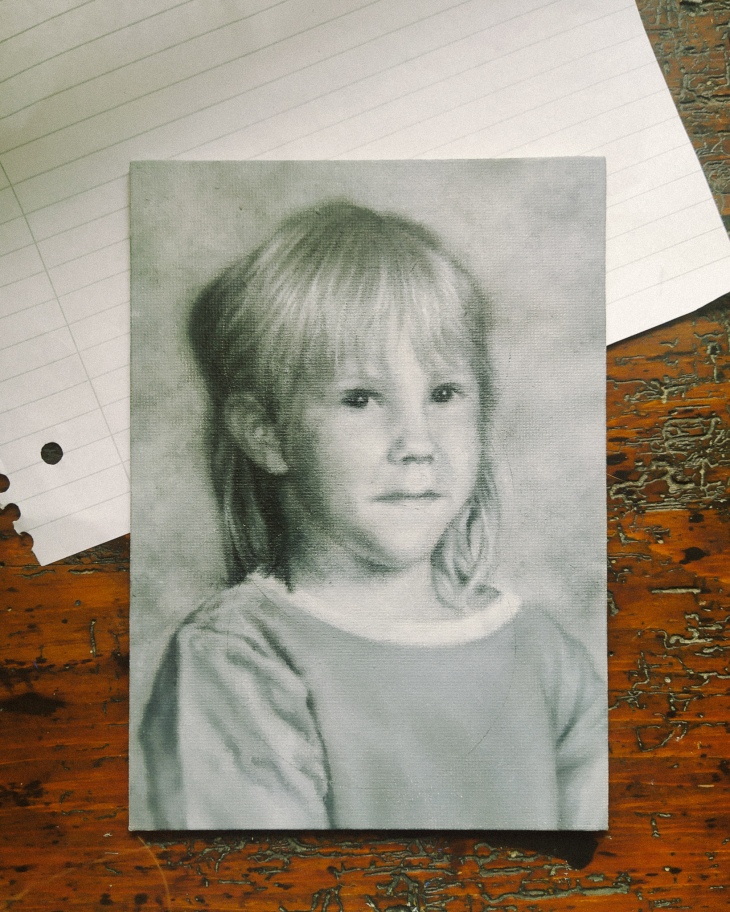

Proximity is a mixed media piece, slightly larger than an A4 sheet of paper, combining two oil painted miniatures sitting within an embroidered frame. The portraits, one featuring a young boy around the age of 7 and the other of a slightly younger girl with her head cropped out, are those of my father and me. In the photographs my painted portraits are based on, we are wearing the same pair of tasselled leather trousers, although by the time I had the honour of doing so, nearly 25 years ago now, they had been cut into shorts.

The reason Proximity took so long to finish was largely due to my indecisiveness. Having finished the embroidered cover, largely using cotton thread and acrylic yarn, I simply could not choose what I wanted to paint. Overtly Covid-centred subjects would have felt false – I am not that type of an artist and everything else seemed too mundane. I left Finland over ten years ago now, but I have never felt this far away from home before. Of all the things I have missed during lockdown: family, friends and my home in France… it was my dad Juha who I missed the most. He’s a typical Finnish bloke, not the type to video chat or hang around social media and I have really cherished our long phone calls during this difficult time.

For better or for worse, Proximity is my main lockdown piece. I have already improved on some of the ideas I first explored with this piece; others I have completely abandoned for now, but it shall always have a special place among my artworks. I turned thirty just a week ago and the most important thing I am trying to implement, having reached this milestone, is to spend less energy on worrying about what other people think of me. I lost quite a few followers off my Instagram when I started posting images of these types of mixed media- and textile pieces, but I’ve gained new ones since. Life is too short to obsess over social media, and not worth living if you are just going to regret every risk and change of direction.

So: take risks, create and don’t lose sight of the things that matter the most – that’s the new normal public service announcement from me to you.

Tiina x